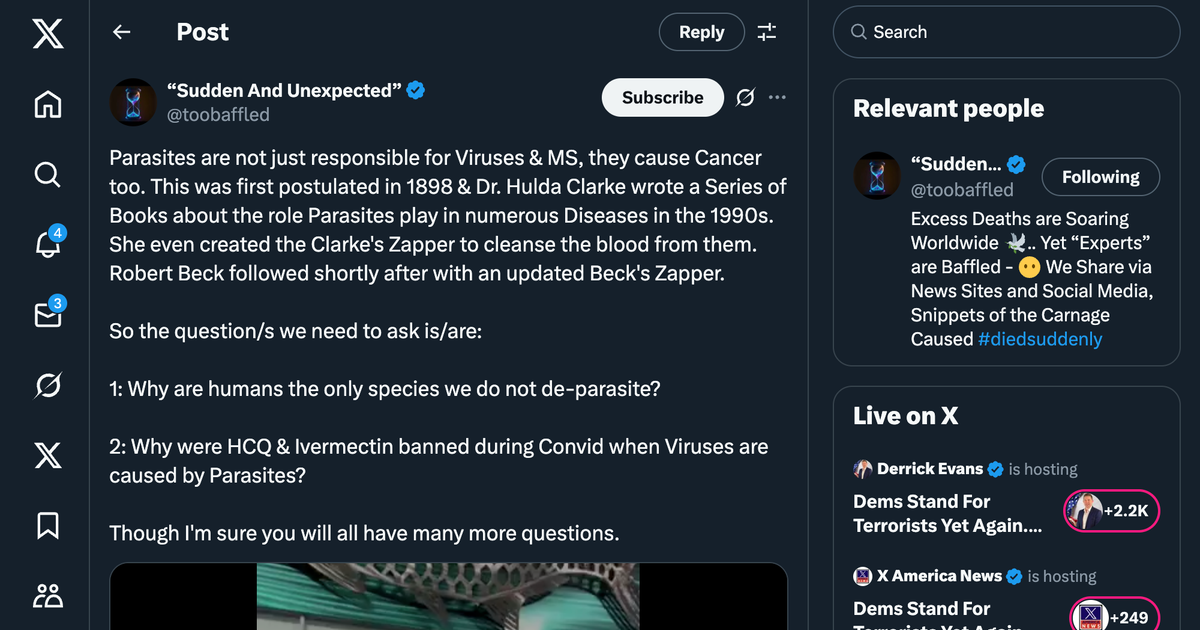

The claim that parasites cause not only viruses and multiple sclerosis but also cancer warrants rigorous scrutiny. Originating in 1898 and later expanded by Dr. Hulda Clarke in the 1990s through her books and the Clarke’s Zapper device, this hypothesis suggests parasites underlie numerous diseases. Robert Beck’s subsequent Beck’s Zapper aimed to eliminate parasites from blood. To evaluate these claims without relying on potentially manipulated secondary sources, a systematic approach grounded in the scientific method is essential.

First, consider the assertion that humans are uniquely exempt from routine de-parasitization. This requires examining primary data on parasite prevalence across species. Veterinary records and epidemiological studies can clarify whether humans face lower parasitic burdens or if medical practices overlook routine anti-parasitic treatment. Peer-reviewed literature, such as studies in parasitology journals, should be prioritized over anecdotal reports.

Second, the claim that viruses stem from parasites, coupled with the restricted use of hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin during the COVID-19 pandemic, demands investigation. Original clinical trial data, accessible via repositories like PubMed or clinical trial registries, must be analyzed to assess these drugs’ efficacy against parasites and viruses. Funding sources, study designs, and statistical outcomes should be scrutinized to rule out bias. Additionally, the mechanistic link between parasites and viral diseases requires experimental evidence, such as controlled studies demonstrating causal pathways.

To proceed, consult primary sources—raw datasets, lab reports, or historical medical texts. Devices like the Clarke’s and Beck’s Zappers should be evaluated through independent, double-blind studies measuring their biological effects. All claims must be tested against reproducible evidence, with hypotheses refined or discarded based on findings. This methodical approach ensures conclusions are rooted in verifiable data, not speculation.